Timing is everything: how exercise shapes metabolic health and brain adaptability

23 September 2025

23 September 2025

Our brain is not the only part of our body that tells time. Each of our organs has its own internal clock and syncing them through food and exercising could be the key to better metabolic health. To investigate this, Ayano Shiba, researcher at the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience, focused her PhD research on how the timing of exercise and eating influences the body’s internal clocks.

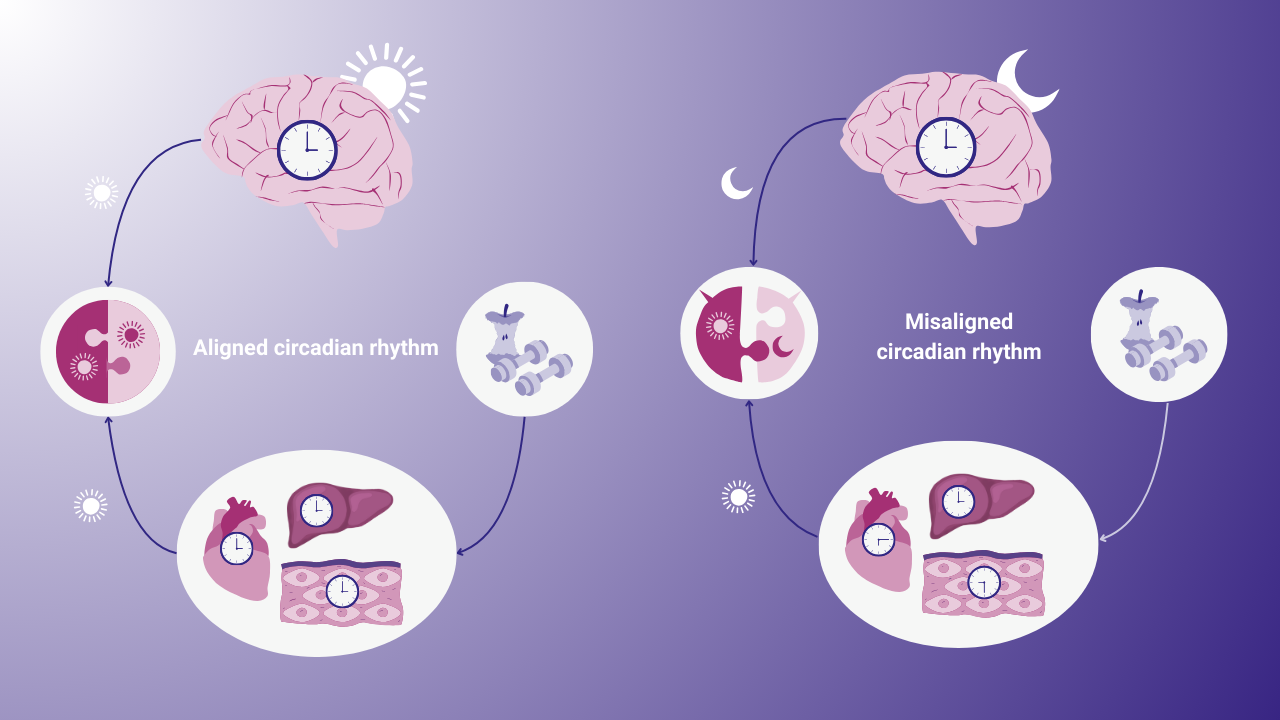

Our internal biological clock is largely controlled by light. Every morning, light enters our eyes and resets the central clock in our brain. This helps us synchronise various processes in our body. But our brain is not the only part of our body that keeps track of time.

In fact, every organ, such as our skin, liver, and heart, has its own internal clock, known as a peripheral clock. These clocks operate using the same molecular machinery as the brain’s central clock to generate rhythms. However, these rhythms are not directly regulated by light, but by behavioural timing cues such as the time we eat and are active. Under normal conditions, when our behaviour is in sync with the light/dark cycle, the rhythms of the central brain clock and the peripheral clocks are also in sync with each other.

However, problems arise when we eat or become active at unusual hours. For example, night shift workers, such as doctors, firefighters, or nurses, are often active at night and sleep when it is bright. This causes our brain to think it is night because it is dark outside, while our liver claims it is daytime because we just ate. This causes a mismatch of information between our peripheral clocks and the central clock, a phenomenon known as circadian misalignment.

Over time, this chronic misalignment can lead to serious health consequences. “Studies have shown that people experiencing long-term circadian misalignment are at higher risk for obesity, type 2 diabetes, and even cancer,” Shiba explains. “Understanding how these clocks work, and how to better align them, might help us design healthier routines, especially for those whose lifestyles force them out of sync with the natural day-night rhythm.”

Our body contains a central biological clock in the brain and multiple peripheral clocks in the organs. Light mainly influences the central clock, while the peripheral clocks mainly respond to behavioural signals, such as when one eats or exercises. In a regular circadian rhythm, these clocks are synchronised. However, eating or exercising at unusual times can disrupt the circadian rhythm, causing the clocks to become out of sync.

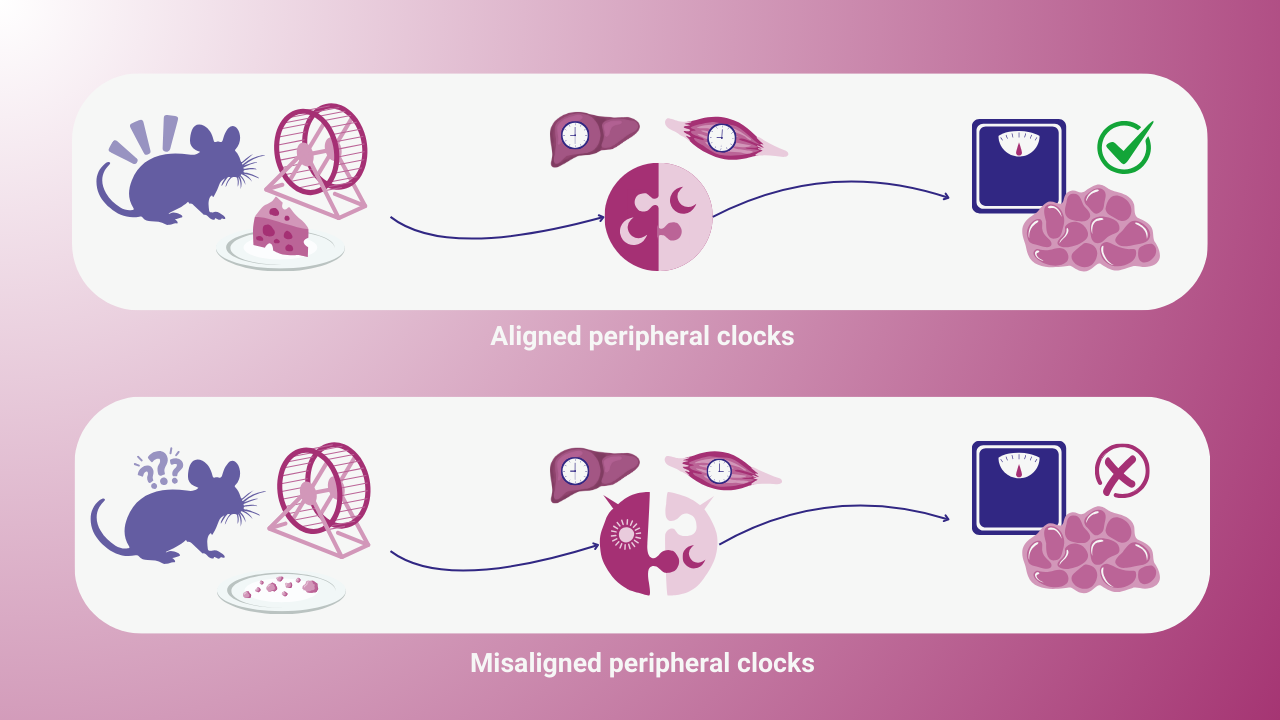

To explore how the timing of eating and physical activity affects our peripheral clocks, Shiba and her colleagues at the Kalsbeek group used rats, naturally nocturnal animals, and exposed them to different behavioural conditions. Some rats had to exercise during the light period, while others could only exercise at night. Some rats ate in sync with their exercise times, while others did not.

Previously, Paul de Goede and Joelle Oosterman, former PhD students of the Kalsbeek group reported that eating at the wrong time of the day (daytime) shifts the liver clock while the muscle clock loses its rhythmicity, causing peripheral clocks to become misaligned.

As exercising is a strong cue for skeletal muscles, Shiba hypothesized that exercising should shift the muscle clock from night- to daytime, but the answer was no. Then, she combined both eating and exercising to the daytime, causing something interesting to happen: both the peripheral clocks of the liver and muscle shifted by a full 12 hours, making them aligned again.

Even more surprising was the effect of timing on the metabolism of the rats. When the timing of meals and exercising was aligned, even at the “wrong” time of day, it had a positive effect on the weight gain and fat accumulation of the rats. In contrast, exercising at the ‘wrong’ time of day, out of sync with eating, was as damaging as eating an unhealthy diet.

“Before applying this to humans, we obviously need more follow up research. However, our results give a good indicator that it is better to align the timing of eating and exercising even at the “wrong” time. If I may be so bold and directly translate this to a real-life situation; Eating a pizza at midnight after partying all night might actually be better than skipping the pizza and eating the next morning instead. Of course, this also means that the next day you should be fasting!

When rats eat and exercise at the same time, the peripheral clocks in the liver and muscles run in sync. This has a positive impact on weight gain and fat accumulation. If eating and exercise are not synchronised, a mismatch occurs between these clocks, with negative consequences for weight gain and fat storage.

The question remained how exercising at different time of day can affect the molecular mechanisms in our brain. To investigate this, Shiba focused on a protein called ΔFOSB. This protein plays a key role in long-term brain plasticity; the brain’s ability to adapt.

Shiba and her colleagues examined ΔFOSB levels in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), the brain region where our central clock resides. They found that exercise led to a decrease in ΔFOSB levels, suggesting greater flexibility in the SCN. “In a broader sense,” Shiba explained, “this may partially explain the mechanism of how exercise helps the body to recover quicker from things like jet lag by supporting the brain’s ability to better reset its internal clock.”

But another key player in the brain’s plasticity arose. When they compared ΔFOSB levels in male and female rats after exercise, they noticed that while exercise caused a small decrease in ΔFOSB levels in males, the reduction in females was much more pronounced.

To understand this difference, they compared ΔFOSB levels and the estrous cycle in female rats. “Interestingly, the low ΔFOSB levels in the SCN coincided with the peak levels of estrogen,” Shiba explained. “Together with the result of the follow up experiments, both exercise and estrogen seem to decrease ΔFOSB, making the brain more adaptable.”

Lower ΔFOSB levels in a specific brain area lead to greater adaptability in that area. Both exercise and oestrogen lower ΔFOSB levels and thus also increase the brain’s adaptability.

This research offers valuable insight into how our central and peripheral clocks function, and how their alignment can influence our metabolic health. These findings may improve advice for people who do not work under normal timing conditions, like nightshift workers.

But beyond the health benefits for nightshift workers, Shiba emphasises the relevance of this research to our modern hectic day-to-day lifestyle: “It feels like that we never have enough time for anything because we are always so busy. We need to work, cook, eat, exercise, spend time with family and various friends, and many more. So, if we can cut corners by optimising meal and exercise timings to ‘improve our metabolism while saving one hour of exercise time a day’, what’s the harm?” says Shiba.

Ayano Shiba: The clock is running – Effects of Timed Exercise and Food Intake on the Circadian Timing System in the Rat.” The defence took place on Tuesday, September 23, 2025 in the Agnietenkapel, Oudezijds Voorburgwal 229-231, Amsterdam.

The Friends Foundation facilitates groundbreaking brain research. You can help us with that.

Support our work